Curated connection: Visual arts alumna and faculty cross paths through an exhibition

Fine arts majors don’t have a traditional career path after graduation. The options are diverse, and paths with other artists often intersect at interesting points.

Audrey Miller, a 2016 graduate from what is now the College of Architecture, Arts, and Design, uses the diverse skills gained through experiential learning opportunities and courses in the School of Visual Arts to curate art spaces for the Workhouse Arts Center in Lorton, Virginia. Her most recent exhibition, "VMFA: Futures," pulled pieces together from the 2022-23 Virginia Museum of Fine Arts fellowship recipients. Included in her selections were photographs by fellow Hokie Michael Borowski, associate professor and the college's interim associate dean for research and creative scholarship.

“When I’m choosing artwork to be in an exhibition, I’m trying to choose artwork that is not necessarily in the same medium or exploring the same topics as the artists on site, bringing additional variety into the gallery space with things that people might not see while they’re already on campus,” said Miller.

As Miller pulled pieces together, an overarching theme emerged. The art explored body and place: Where things are, how they feel, where people are from, and why that matters. Miller found Borowski’s photography and artificial intelligence (AI) generated images of mineral springs interesting, not realizing he was a Virginia Tech faculty member until after she included them in the show.

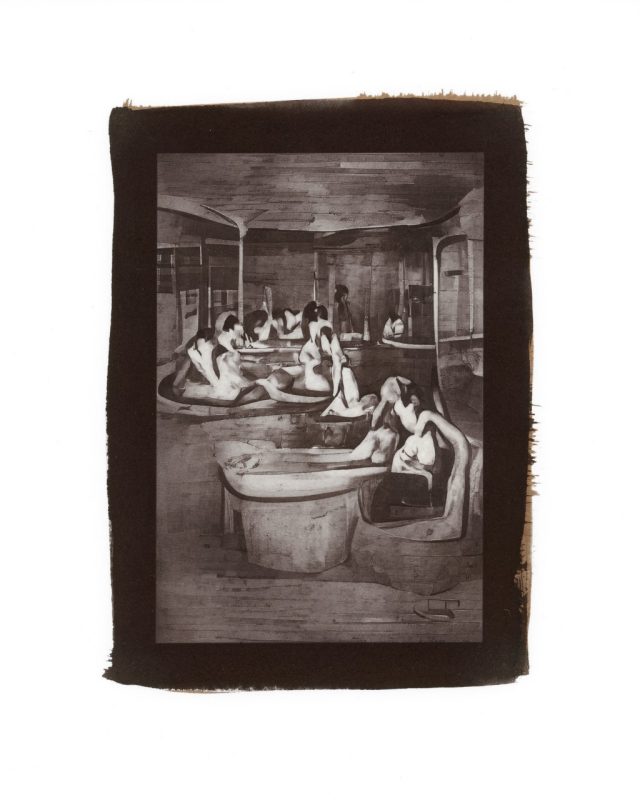

“Michael Borowski’s photography is a transformative work, combining AI artwork brought into 3D space by using a salt print technique, the primary way that photographs were printed in the 1800s, the time his body of artwork referenced, and I thought that was really fantastic,” said Miller. “It just so happened that he was a photography teacher at Virginia Tech, and I graduated from there.”

Borowski researched the history of mineral springs, photographing what remained of various sites. His research interests also include queer history in Virginia and the South. Because mineral spring baths were assigned by gender, he thought there might be something new to discover by combining his research areas. There was no recorded LGBTQ+ history of these spaces, so Borowski used an AI tool to create images of a fictional mineral spring, representing this missing history.

“You put in text prompts, so I might type in 'mineral spring' or 'spa' or 'locker room,' and then there is a diffusion process where you see the image emerge,” said Borowski. “I probably generated 100 of these and then edited down to about 20 that were interesting. Those are the ones I made prints out of.”

Borokowski then incorporated a photographic technique used in the late 1800s called salt printing.

The salt printing technique includes

- Making the digital image into a transparent negative

- Coating the paper with two types of chemistry, which makes it sensitive to UV light

- Putting the negative directly on top of the coated paper

- Exposing the negative to sunlight or a UV exposure unit

“The thing I love the most is how these shapes kind of look like bodies in a bathhouse or hot spring from the corner of your eye. Then when you look closely, they don’t make sense. I talk about that being my experience looking for queer history. It seems like there might be something, but when you start to dig, it becomes harder to pin down,” said Borowski.

Visual arts have always resonated with Borowski. Rather than speaking his ideas, he found comfort in creating something for others to view. As the interim associate dean for research and creative scholarship in the College of Architecture, Arts, and Design, Borowski works with faculty from all creative fields who are responding to the world in a variety of ways. Together, they work with students, helping them find their voice and the form of expression that “speaks to them.”

“It’s a chance to make sense of the world, sharing how you feel about it, what’s interesting to you, or what you’re fascinated by,” said Borowski. “Some fall in love with photography, and others want to be in the sculpture studio or interact with different materials and equipment that speaks to them more. It’s exciting to see people find that thing that feels like a good match.”

For Miller, curating an art space is about bringing those different voices together to engage the public in perspectives and opinions for their consideration.

“Even if you don’t agree with what the artist has to say, hopefully viewers can appreciate the way the artwork is presented and come away thinking about it differently. You don’t always have to accept the things that you don’t agree with, but you can take something away to digest later,” said Miller.

The career path after graduation for fine arts majors may not be as direct as other disciplines, but the diverse skill sets students gain offer a variety of choices, including art therapy, education, and gallery work. Miller remembers lectures and courses that she believed, at the time, didn’t apply to her personal goals. As the visual arts manager at Workhouse, she is grateful for her education.

“Professional practices, the exhibition design class I ended up taking, and the experience of having my senior exhibition are probably the reason why I have this job,” Miller said. “You aren’t pigeonholed as an art student to only creating art. There are other careers within arts management and administration, and other avenues to go from there.”

“Faculty hope that their students make time to create their artwork no matter what career they pursue, which is the core of what we try to teach, taking your experience of the world and then turning that into something visual to be shared with others,” said Borowski. “That’s the thing I love about the arts.”